Chances to try again come in many guises. For me, they often arrive during flurries of mad activity and desperate effort; opportunities have sometimes been hard to spot because I fly past in such a harried rush. Middle age and officialdom have provided some antidote to this tendency, though. I have slowed, and the stakes have grown more emphatic, harder to miss. In case I am still oblivious, I am gifted signs from heaven and earth, if I care to credit them.

(Carmen kneels in the front row, second from right, wearing white blouse and red dirndl)

I am American by birth. I was there until I was 42 years old. A whole life was lived in those years – marriage, motherhood, a business, houses, cars, friends, and extended family. I held my part of it together as many others do, with a hope and a prayer and increasing despair. When those no longer served, I ran away to England.

Running TO something, not just away, seemed like salvation to me. I knew that a university degree would improve my chances of being able to support myself; I could earn one in Britain in three years instead of the four that the same process would require in America.

A little hurry seemed good thing since I was starting so late. I had a support system in England – there was extended family living in Liverpool, and a friendship from my teens that had been renewed. Together, they provided some sort of a social net. The English language was just about within my grasp, too, unlike any of the other languages spoken in places that I might want to be. I sold my car and my share in the house, packed three suitcases, put my remaining things in storage, and made (what I hoped would be) a clean, surgical severance from my wounded life. I lost parts of myself, but with those losses came the chance to try again. Better an amputated limb than still stuck in a trap.

For three years, I was a ‘mature’ student at Oxford Brookes University. I graduated with first-class honours in history, a prize for my dissertation, and the history department prize. It was another ending, in a way. But I had made other beginnings while I studied for my degree.

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

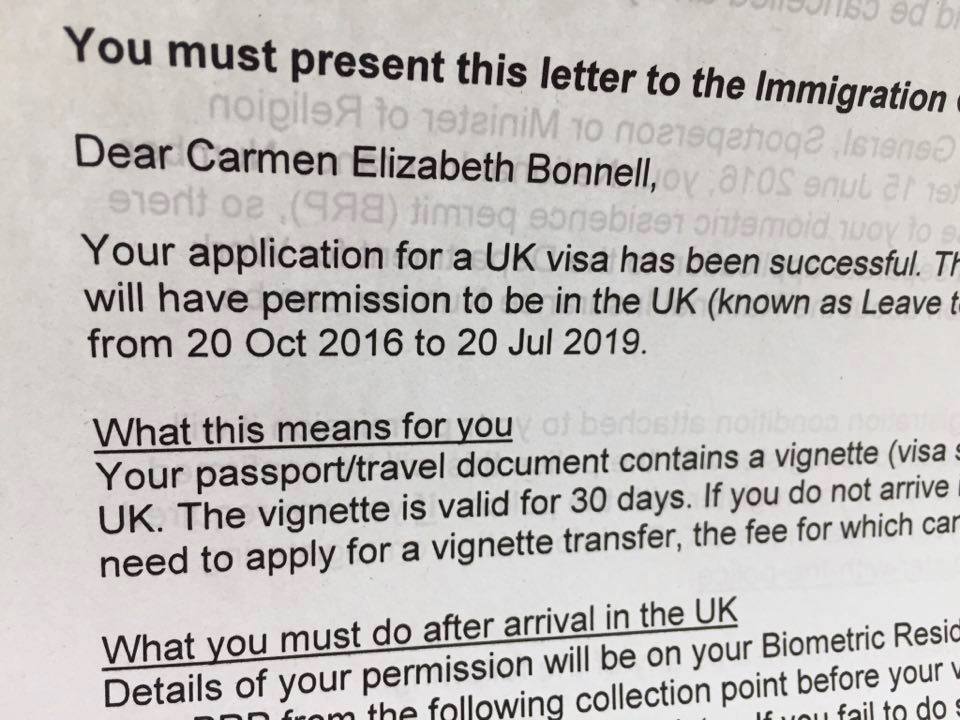

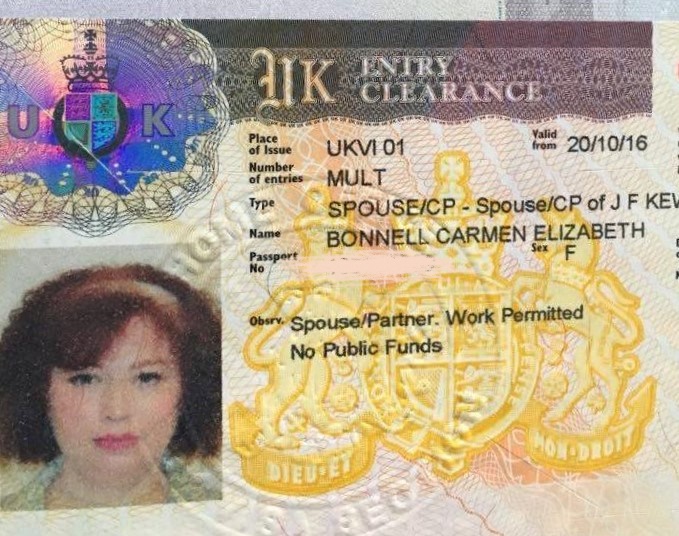

When my student visa expired after three years, the “friend” that I had met during the summer I was 16 decided he would like to keep me – as more than a friend – now that I was 45. I wanted to stay. Our lives had become intertwined during our years of sharing a home while I studied. We hustled to Visas & Immigration, gave evidence that we had a real romantic relationship, documented that he could support me, and proved once again that I was not a criminal. My visa came through with little fuss, if a lot of bother.

There was a great deal of personal drama during the next few years. His mother died. I was diagnosed with coeliac disease, then endured two surgeries to remove agonizing, long-suffered abdominal adhesions. A dearly-beloved family member made a nearly-successful suicide attempt. In the midst of it all, we missed the administrative date to renew my visa. We caught the error before a black mark could be put on my record, but to avoid being in violation, I had to leave the country while my new visa was processed. It was a long four months.

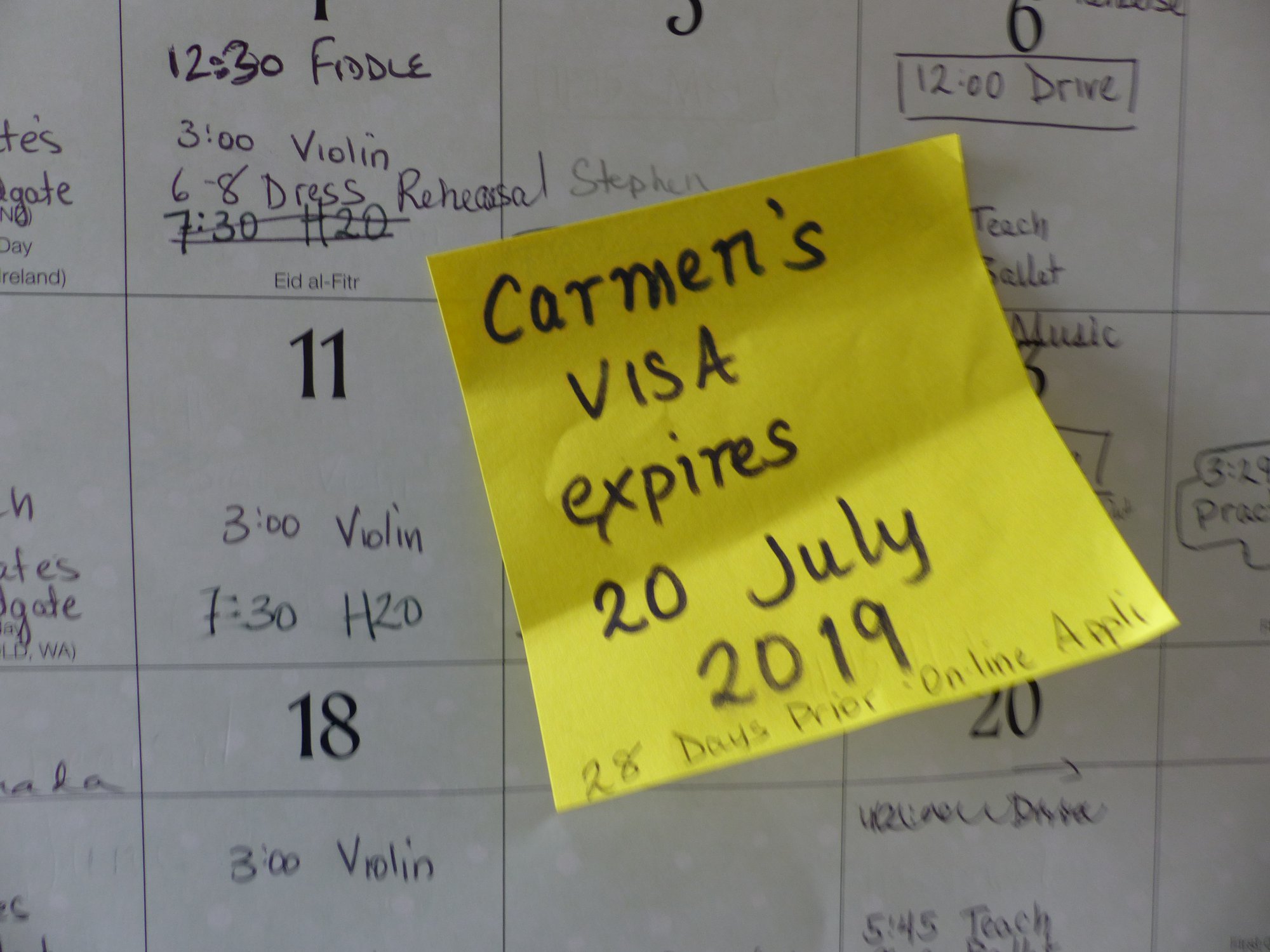

My fresh spouse-partner visa (the UK government making no distinction between the married and the unmarried) was approved at the end of October, 2016. I returned to England during the first week in November. Once home, I wrote the date for my visa renewal on a sticky note in large, clear letters, then transferred it to every fresh page of the calendar until it was time to act. I never wanted to live through a mistake with my visa ever again.

I also proposed to my partner. The muddled grey area that our relationship status existed in was no longer appealing; I was tired of making impossibly complex explanations in every social situation. The storybook romance needed a happy ending so that we could go on to the next book in the series. I was a little overwhelmed when I discovered the amount of administrative work this simple decision required, though.

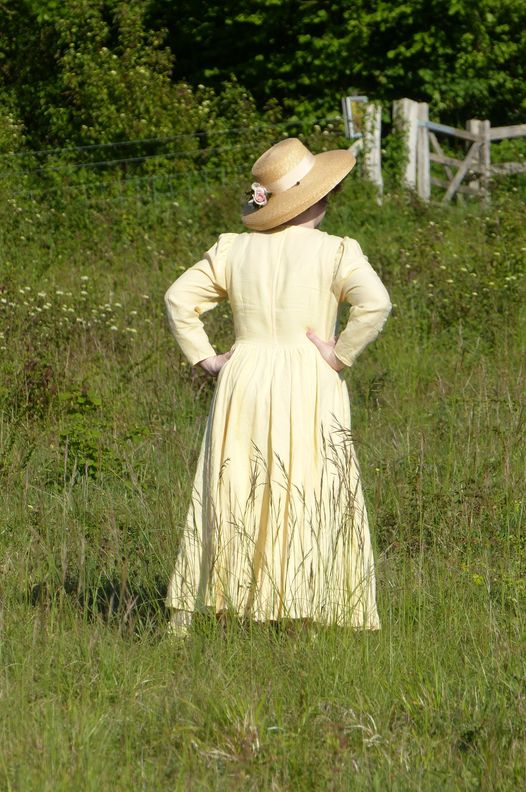

Though officially in England as his romantic partner, we had to apply to the government for permission to wed. The wait for approval felt interminable. When permission came, we found that my immigration status meant we had to pick between a limited list of registry offices for the event. Still, I had no desire to play Princess-for-a-day or spend vast sums of money on a splashy event. All I really needed was the man, the license, and an officiant. As it was, I had time to make a dress for the ceremony. At last, in March, we married.

Being back in England and the childhood-romance-come-true were only parts of life. What came next might have served as a distraction from remembering the visa application. I was extra careful.

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

I was diagnosed with breast cancer within days of my return from America. The lump must have been there during all the medical treatments I received before I left England, but we weren’t really focused on that part of my anatomy. I found it, all 20mm of measurable mass, during the first week of my exile. I told no-one because there was nothing anyone could do. But I maintained a rough method of monitoring the tumor’s growth so that I’d know if it was likely to be a problem. It was.

The NHS, and then private insurance through my husband’s work, moved quickly and efficiently. A 22mm tumor and several lymph nodes were surgically removed in December. After time to recover, there was surgery to install a chemotherapy port in February. By the time of our wedding in March, I was in chemotherapy. I found a lovely little vintage hat to cover my bald spot. Months of chemo, radiotherapy, and herceptin injections, and a final surgery to remove the chemoport stretched before me. But I was determined that nothing would keep me from renewing that visa on time.

Spouse/partner visas in the UK are issued for initial period of 30 months, after which they must be renewed. The pile of documentation is several inches thick. Fingerprints and photos go on record. My next residence permit photograph was taken on the day of my final radiotherapy treatment. I look slightly fierce and very tired, but in a way, I welcomed the timing. It was another clear line drawn around a very specific, finite time in my life. With that portion of cancer treatment and that application finished, I started the second – and hopefully final – period of limited residency.

The kind doctor who signed off on my final radiotherapy treatment said I didn’t seem like the sort of cancer survivor to go climb Mt. Everest or anything mad like that. But he did insist that I go do all the things I’d planned to do but hadn’t. ‘Go make a life. Write a book or something!’, said he. My husband and I looked at each other and burst out laughing.

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

Of course I’d always meant to. Anne of Green Gables is my heroine of choice. I read everything, all the time, everywhere. Poems and stories and letters and essays flowed from my pen in my teens and 20s, then got written and stashed in my computer during my 30s and 40s. Pretty journals and fountain pens are my one weakness. Twenty years ago or so, I wrote reviews for a folk music magazine and sold a single article to Mothering magazine. A photocopy of the $100 check they paid me was pinned above my desk for years. My life hadn’t had much time to pursue dreams, then, though. Now, it was doctor’s orders.

I toyed with the idea of going back to study for an advanced history degree. It would certainly involve writing. I contacted Chichester University. Their history programme provided a good fit with my interests in early-modern domestic and material history. We exchanged emails, and got as far as the department head giving unofficial consent to act as my advisor for an MPhil/PhD. I started the application process in earnest.

Then I found, to my great dismay, that even though I was finally eligible for resident’s tuition rates, I was NOT eligible for educational loans in the UK. There was no external funding available for the same reason. It made the whole thing seem overwhelming: tears were shed. Then coronavirus hit, the UK went into lock-down, and I had to face the reality that, even if we spent the money on university fees, it was a REALLY bad time to be attending classes or doing archival research.

So, I stepped back. I diverted. If you can’t go over or under something, you go around it. In the end, I made the decision to enrol part-time at the Open University for an MA in Creative Writing. The OU was already set up to run through distance learning; I felt that traditional universities might be scrambling to figure out how to go about on-line teaching while they would already have it sorted out. For a Creative Writing degree I could do most everything that needed to be done from home, a distinct advantage in the time of plague. Part-time classes made it possible to spread the cost.

That decision made for hard work. Academic writing, which is what my history degree trained me for, is not what they want in this programme. My exhaustive research for each project tends to get in the way of making the words pretty, yet I scrabble for ideas without it. I opted for Creative Nonfiction, thinking it would equip me to write biography, but style requirements are era-specific, and right now they want the writer’s ‘self’ to show no matter how many facts you assemble. My practice of the past decade, as an immigrant wishing for anonymity and a middle-aged woman wishing for peace, had been to attempt nominal invisibility.

After the initial shock, though, I began to see the sense of it all. To apply the wisdom, though, I had to excavate a ‘self’ I had tried to abandon. I had attempted to leave most of my history behind when I left America; much of it was painful. I saw no way to re-claim the precious things, the good things; they were irretrievably lost. Admitting how bereft I felt seemed like a form of ingratitude for the great blessings I had found in my new life. All of it was too complicated to explain to new friends, or myself, and it tended to make me cry when I tried. So I had set a determined course of creating new memories, learning other skills, and becoming someone else entirely.

Still, I did my best to assimilate our course materials. Six assignments in, more than half-way to the final MA project, I finally wrote a piece that successfully played with personal memories and perception. I allowed a little of my internal life to show. It was the first time I wrote without stacks of history reference texts piled around me. I struggled to know what to say when stripped of that veil, though, for I had made too many constrictive rules for myself. I even avoided the topic of cancer, initially, because it seemed like a cheap ploy to pull in the pity ticket. Such are my irrelevant ethical quandaries; I know I’m silly. I am teachable, however.

The story that resulted felt true and good. On faith (though not much) I sent it out into the wide world. Asking to have parts of yourself rejected is part of becoming a ‘real’ writer, or a ‘real’ anything else, I suspect; they tell us to expect 100 rejections for every one published piece. I have taken that to heart, if sulkily. My husband helps – he finds likely venues, and hits ‘submit’ when I can’t quite bring myself to commit. He grins and asks me how close I am to the 100 mark when I get another, ‘Thank you for your interest…’ response.

This process is part of the re-making of myself as the person I think I might have been, a necessary pain if I’m to do the sort of growing up I still think possible. I’ve tried to start from the place that I stalled the first time; I’ve gone back to the last place I could see the path. I reckon I understand some of the frustrations teenagers experience again, even though I’m 53. It isn’t all about hormones. There are just a great many decisions to make, and none of them seem obvious or easy.

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

While I’ve whiled away the time over the past eighteen months in agonies of artistic self-examination, my visa clock kept ticking. Thinking ourselves well ahead of any deadlines, my husband decided to re-acquaint himself with the various regulations and requirements for my next application. It was particularly important to get this right this time, for if granted, I gain the right to remain in England without further administrative work. Any confidence we had in our diligence was rapidly shattered, however. Rules have changed, again.

There is now a test. It isn’t given when you apply for citizenship – oh, no. It is given to unsuspecting middle-aged women who are in the middle of academic programmes when they apply for their spouse/partner visa renewal. It has to be done before you can send in the application, in fact, and there is a waiting list for test dates. You can’t go on to the next phase of the application process until the test is completed successfully.

The interval between scheduling and test proved necessary, however, because my husband – with fifty-odd years of educated British life under his belt – failed the sample test. He took another one and passed it. Then he failed another one. I had been fairly relaxed about the idea of an examination, thinking that my decade in the UK and degree in history would be sufficient. Now, suddenly, it became a matter of urgency to study. I set everything else aside and crammed, trying to channel my fear into work. There wasn’t enough time for several re-takes: my visa would expire. I am not a pub-quiz sort of person, and that’s what this test is. I knew I would stay or leave because of it. I studied.

I passed. I now know how long the Bayeux tapestry is (70 meters), what British film franchise grossed the highest earnings (James Bond), and what time pubs open (11am). The aging computers at the test centre refused my attempts to re-check my answers before I submitted, so I’m sure I missed a few. I’ll never know which ones or how many. They only tell you if you got a pass or a fail. Possessed of a pass, you then get to start the next part of the application process. That’s what I got to do.

Biometrics have been a large part of my life since 2010. Evidently, fingerprints, pupil measurements, and photographs must be done and re-done, and the UK and the USA both want their own versions on record multiple times. I needed an appointment, in person, at a centre in London. The earliest cost-free one (the price becoming exponentially greater the sooner you need it) left a scant five days before my deadline. We grabbed it. The night before, I pulled an all-nighter to get an MA paper submitted; I was nearly incoherent with fatigue. But husband got me to the right place on time, and I spoke in full sentences while it was necessary. There were only minor complications.

My ears are a problem. They lie too close to my skull and are therefore difficult to photograph. Ears are an identifying feature and important to the official records of immigrants. The logical thing would be to take the picture in profile, but this is not allowed by the regulations. It caused some moments of consternation, since there was no real way to fix the issue. Also, my fingerprints are somewhat smudged by years of playing the harp: I have blistered and callused repeatedly, and it isn’t good for the definition of my ridges and bumps. Or perhaps it was just that I had put on hand-cream during the hour it took to drive there. In any event, the photograph-and-fingerprint routine had to be repeated three times before we were done.

The courteous young man asked me, finally, if I was happy to submit my application, and then asked again, to be really certain – causing me to nearly shout, ‘Yes! PLEASE. Yes – submit it! NOW!’ It felt like we were running out of time.

The visa application has been submitted. It exists in the void of officialdom. It may be a six-month wait before I get a response. I am trying not to think about it.

On the way out of concrete, dispirited, rain-sodden London (Croydon, not the pretty, touristy, history-laden London of my American fantasies), a rainbow filled the sky. I know it is trite, this sign-of-hope trope, but there it was. It did feel like a message. Dingy buildings can be quite glorious when draped in gem-hued dazzles.

In the tentative spring days since, we often seek the peace of our own patch, the familiar places. Solace is there, tucked into the land. We know a certain hollow that the butterflies favour. It is early, but they are sometimes seen on warm days even in March and April. Among the (to me) wonderfully exotic array of English butterflies is the Comma. We don’t see them often, even on concerted hunts, but they are the perfect token of serendipity for a writer-in-training. One day, almost without warning, a pristine, colour-infused Comma scuttled through the air before us, then settled. It sat long enough for my husband to photograph it. ‘Maybe it’s a sign,’ I said. ‘Perhaps that piece will get published.’

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

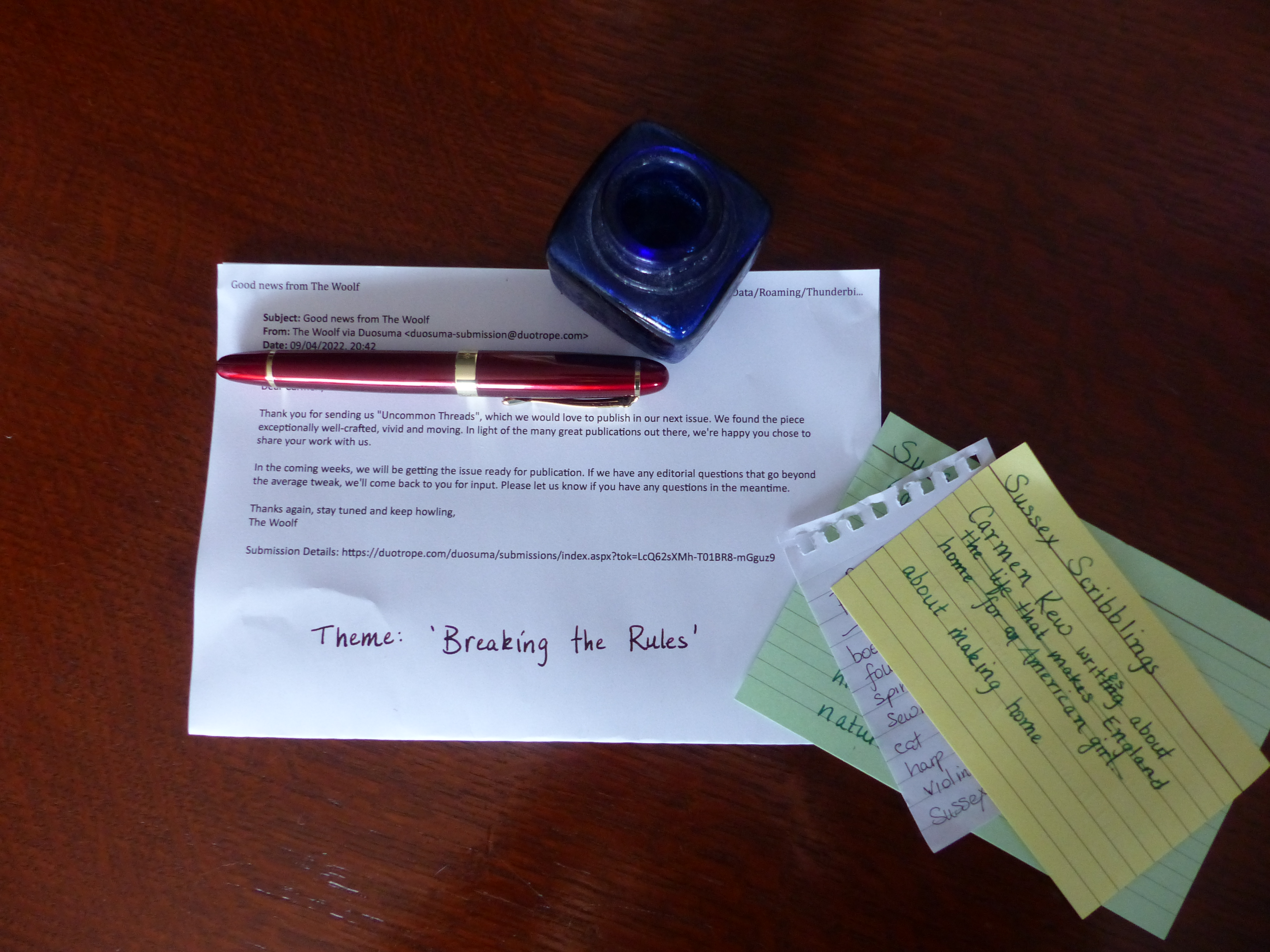

I nearly deleted the email. It looked like a marketing ploy. ‘Good news from The Woolf’, reads the subject line. I skimmed it, then read more carefully. I read it again, then cried out and danced and jumped up and down and became nearly wordless in trying to explain why I should be so affected. My commas have found their own resting place, flight in the wider world, and that still seems disconcerting and unreal. In the next issue of online publication The Woolf, they say, I will be transmuted into a ‘real’ writer.

So, I will continue on. I will write, and throw away more than half the words. I will agonize over how much to tell, and over what is right to say, and still will say too much and yet not enough nearly every time. I will write the vast, unknowable expanse of the MA final project, a deadline coming too soon and not quickly enough. I will send my words out into the unseen universe to see if they resonate with others. I will wait, sometimes patiently and more often with a subdued sense of worry, for news of my visa. Someday, I may be able to apply for British citizenship.

I will tell myself that this is what is needed: to apply myself to life, and then to submit to what follows. Application will ingrain the knowledge and habits I need to become a writer. An application means I am one step closer to calling England a permanent home. Submitting my writing for publication brings me enough rejections that someday, more pieces will be accepted. Submitting to conscious memory and the pain of loss will allow me to reconcile who I have been with who I am now, and allow me to be more than just one or the other. In all things, I must submit to waiting, to not knowing what the end might be, to learning new things and forgiving my own childlike uncertainties and fumbles. I must apply myself to learning to walk between fear and hope.

It helps to tell this story to others. Mostly, though, I know I write for myself. With words on the page, I can chain together the meanings in rainbows and butterflies. I can see a the flutterings of a possible future.

Fairmile Bottom nature reserve, West Sussex, UK

So glad to read your first post! YOU DID IT!

LikeLike

It is SO appropriate that you should be the first to read it and comment! The story wouldn’t be the same without you in it – I hope you hear all the unstated gratitude.

LikeLike

I’ve always known you were special. How could you not, arriving the tge day and year of my graduation from Curtis High School. You, the daughter I wanted so fiercely after so many boys in this family of Goidwins. Neither of you have ever disappointed as individuals with integrity, grit and the gift of being decent, wonderful women

LikeLike

Thank you for being an ever-present source of love and good faith, dearest of aunties! You have made yourself available when I’ve needed you most: you know so many of my stories. Now, it’s time to use that support to move forward!

LikeLike

So glad to know you are writing again! And there is something about growing older that causes growth and reflection on who we are and where we came from that is healthy and good. I look forward to reading more!

LikeLike

I am so glad to find you ‘here’, Sandy! There are some people that are lynchpins, reference points, and grace. You are one of those. There HAVE been good things and wonderful people, and I want to celebrate that. Joy comes with sorrow; the two things can be hard to disentangle. So, instead of trying, I shall just go on!

LikeLike

Carmen…you are an asset to the creative life of the UK! Thank you for sharing your path here

LikeLike

As are you, Victoria! Your wonderful smile and warm welcome have made all the difference, many times over. I’m so glad we’ve been in the right places at the right times to find each other!

LikeLike

Wonderful writing …. so characterful and engaging. Thank you for sharing your story.

LikeLike

Wonderful writing …. so characterful and engaging. Thanks for sharing, Carmen. Fingers firmly crossed for the visa app. What is your choice of celebratory music when it arrives?

LikeLike

I have this fantasy that the visa will come in time for our Open Rehearsal at the end of term. Then ALL the music would be perfect! Since I know that’s unlikely, I think I would ask YOU to pick: you’re still providing my British music education, after all. I still am but a child when it comes to English repertoire, and will be for some time to come!

LikeLike

You have always been so brilliantly you.

The fantasy, the character, the life-energy, the unique charm, both aspirational and truly humble. They were all already somehow present in that little girl in the dirndl that I knew and have always so deeply appreciated.

There was no way that she could, in any way, comprehend the challenges that lay before her. But those core-qualities have allowed you to adapt, survive, make a stand and thrive and now, with your life-experience and the encouragement to share some of yourself, the blessing of your expression may also touch others who have never enjoyed the pleasure of your company.

Your true story is inspirational and your stories let it be told.

The adventure continues…

LikeLike